Teaching Notes on M. Kempe, 2020

Taught The Book of Margery Kempe again, this time for my MA version of my Irrational Animals course. Perhaps the chief surprise in my fourth? fifth? time teaching it was the two papers I received on marital rape in The Book. The key passage for each paper was “And in al this tyme sche had no lust to comown wyth hir husbond, but it was very peynful and horrybyl unto hir” (And in all this time, she has no desire to have sex with her husband, but it was very painful and horrible to her; Book 1, Chapter 4). On the one hand, this chapter aims to separate Margery from her life as a sexual being: if one of the Book‘s goals is to render a married woman sanctifiable by purifying her from the taint of sex, then the Book has to show Margery as first tempted by sex (as she is in this chapter), and then repulsed by it. But my students — perhaps laudably free from the “baggage” of the habit of historical contextualization — noticed immediately that John Kempe must have been raping her. With that in mind, the students argued, for example, that her visionary experiences, however irrational they might appear to many of us, could be understood as a perfectly rational mechanism for freeing herself from her husband. Outrageous unrecognizable crimes need an equivalent countermeasure. As I said to the student:

That said, one other thing I like about your paper is that it recognizes Margery’s ‘fits’ as also having a rational goal: in your reading, she’s not simply an outrageous noisy woman, but a woman seeking her own liberation by enthralling herself to forces more powerful than her husband and his masculine social order.

The irony, as the students variously observed, is that her “rapture” (from raptus, the same etymological source as rape) by the divine is a further disruption of her consent. Saved from earthly rape, she finds herself — like Chaucer’s Criseyde, I’d say — in something frighteningly similar.

As I also observed to them:

On the one hand, I’m very much in favor of historical contextualization for Margery — otherwise, we will mistake a great many things as strange that would have seemed to people of her own era as not that unusual for someone who’s practicing the kind of mystical spirituality Margery aims at. After all, the one complete surviving manuscript of the work was read, apparently without disapproval, by a quite severe order of monks. But that historical contextualization can also have the effect of erasing Margery’s individual physical presence and the experience of her own life. And that, I’m increasingly convinced, would also be a mistake. I’m not sure how to balance these two elements against each other, because the issue this question raises is, essentially, where do we find the individual amid historical and cultural forces? And *that* question is so very very difficult to answer!

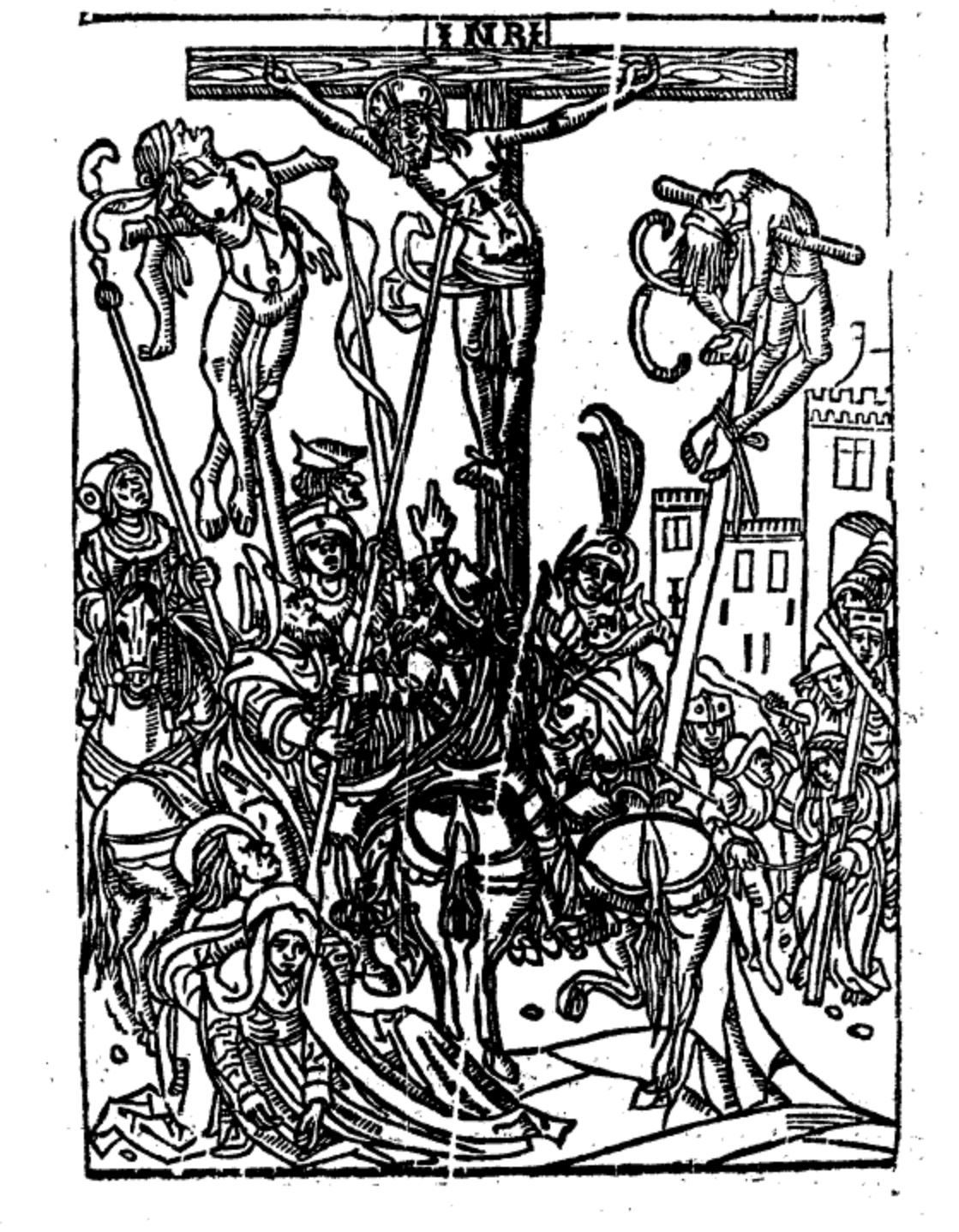

And if we lose too much of Margery, well, we end up with something like Wynken de Worde’s 7-page Here begynneth a shorte treatyse of contemplacyon taught by our lorde Jhesu cryste, or taken out of the boke of Margerie kempe of lynn, whose first page I offer here from EEBO:

Although even the bowdlerized Margery isn’t enough to satisfy the haters. In the second volume of his expanded edition of Joseph Ames’ Typographical antiquities, the bibliographer Thomas Frognall Dibdin (d. 1847) observes:

The following short extract, in modernised orthography, may serve to shew to what an inflamed pitch of enthusiastic rapture and gross absurdity some of the devotional treatises of this period were wrought. (363)

With slightly updated vocabulary, and streamlined syntax, Dibdin’s 1810 judgment on Margery can still be encountered, and not only in our classrooms.

Also: in the course of my comments on their papers (which were also, depending on the student, were on Foucault’s Madness and Civilization or Hoccleve’s “Complaint”; none, disappointingly, were on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Life of Merlin), I thought with the students about the degree to which Margery actually goes against her society. She does, of course, in that she’s a woman taking on a role as a spiritual leader. And she does, in that so many of the people she encounters find her deeply unpleasant.

But unpleasantness does not mean that she’s “wrong.” The interesting thing about Kempe is that she becomes unpleasant precisely by living out the fundamental religious beliefs of her culture more authentically than anyone else; she takes them seriously, and the others don’t (one student last year drew on the example of “drive through” Ash Wednesdays). So, it’s not so much that she’s a ‘maverick’ and a ‘free thinker’ and all these other categories of social obnoxiousness that tend to be applied to men as praise. Although she’s accused often of being a “Lollard” heretic and even a Jew, she handily refutes all of these charges of wrong belief, demonstrating repeatedly that she believes exactly what all the Christians around her do. It’s thus less a matter of her ‘going against’ then than of ‘going further’.

The problem with Margery is not what she believes, then, but how she practices it. That is, as I observed to one student, what we’re discovering in The Book is that religious difference can be a matter of differences in belief, but differences can be much more disturbing when they concern clashes over forms of worship, so that even a ‘doctrinaire on paper’ Christian like Margery can look like a heretic because she’s worshiping wrong.