Does Cruelty Necessarily “Dehumanize”

(My MLA 2025 paper. Sat 11, 10:15-11:30, Royal, 3rd Floor Hilton, “Thing, Text, Human”)

We were asked to talk today about changes to the idea of the human in an era of rapid technological changes. I’m not going to meet that requirement, because I’m not sure yet I know what we mean by “human.” My concern, rather, will be with “dehumanization,” a word that we can’t help but repeat, desperately, in our era of seemingly ceaseless catastrophe.

When “human” is used in this context, by no means does it point to us as the mostly hairless bipedal primates: to be hailed as a homo sapiens is somehow precisely not to “humanize.” Because to “humanize” is to recognize the other not as a biological being but as a thinking and feeling one, desiring and desired by others, with a sense of dignity, family, and lineage. The at least implicit point is that were people treated as human — or as the phrase often goes, as “fully human” — they would be spared whatever harm is being done to them. The presumption, a variant of the Golden Rule, is that we like ourselves, and want no harm to come to ourselves, and that therefore we should see other people as ourselves, because then we would want to spare them harm. As you might expect, I’m here to push back against this, because it strikes me as a sentimental fantasy.

Because I am a literary scholar, I have a test case; because I’m a medievalist, it’s from the late fourteenth century, a nearly 1400-line Middle English alliterative poem known as The Siege of Jerusalem. The poem restages the Roman assault on Jerusalem as anticipation of the Crusaders’ bloody seizure of the city a millennium later. Barring Nero, the Romans convert to Christianity, so their assault avenges not so much Rome’s dignity as Christ’s, whose crucifixion is figured here, as it was so often, as the fault of the Jews. Christ’s death gets only small attention; the poem devotes itself instead to the assembly and splendor of armies, the healing of bizarre ailments — Vespasian is so called because he has wasps in his nose, which only Christianity can drive out — and especially to spectacular scenes of violence. My regrets for what follows: in it, we have heads smashed by siege engines, heaps of corpses immolated, their dust hurled as poison into the city, high priests flayed alive and hanged with biting animals, prisoners disemboweled to loot them of swallowed coins, and a mother driven by starvation to cook and eat her own child. It’s horrific, overwhelming, but also undeniably highly wrought, a fine example of alliterative craftsmanship. Criticism is ample, and often concerned with what seems to it a strange combination of delight in Roman triumph and sympathy at Jewish suffering.[1] My brief point here is that I don’t find this mélange so strange.

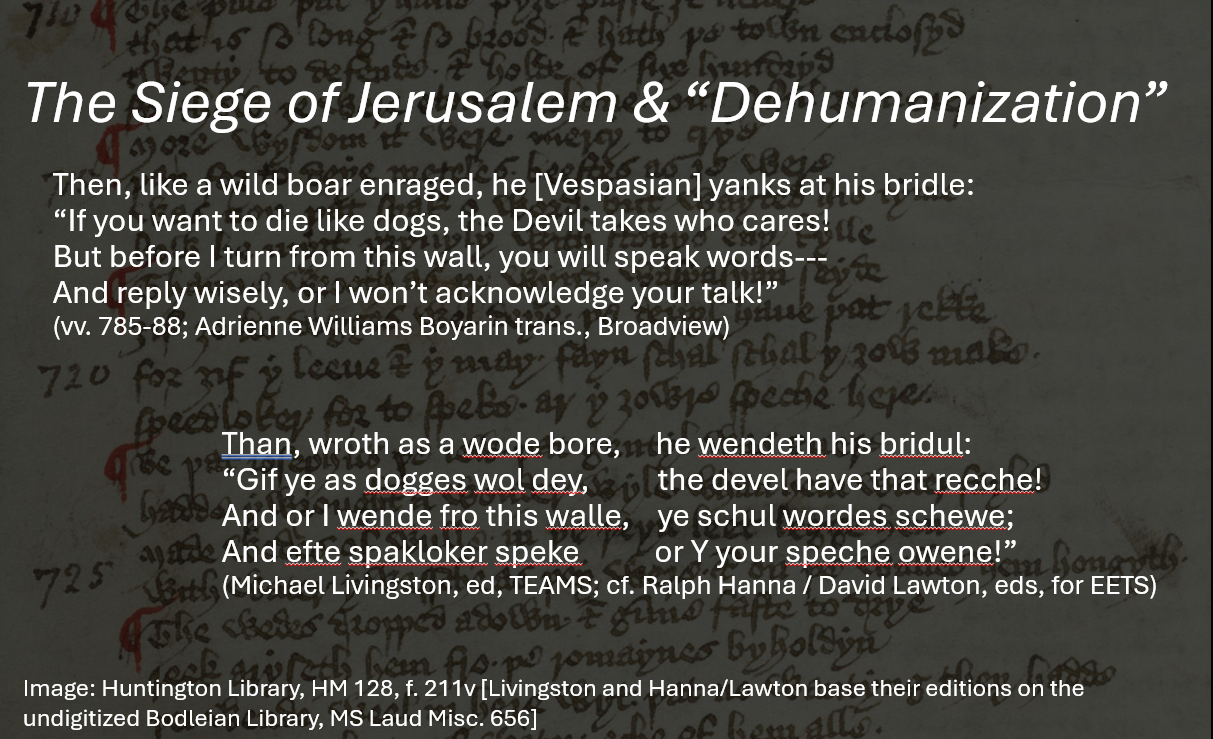

We have time for one stanza. Vespasian has besieged Jerusalem, cutting the Jews off from food and water. Starvation sets in. He offers them surrender, bluntly: “If you want to die like dogs, the Devil take who cares! But before I turn from this wall, you will speak words — and reply wisely, or I won’t acknowledge your talk!”[2]

At first glance this seems simple: the stanza contrasts human speaking to animal death. The reasoning animal can parley; it can be offered mercy, or at least a contract, as otherwise, it will die “like a dog.” Humans on one side, animals on the other, and what Vespasian has done, in a way, is to offer the Jews a choice what they might be. We see this division hinted at elsewhere. As the siege creaks to a close, the Jews turn on each other “like wolves” (1079); Domitian destroys a Jewish raiding party as if they were “all like beasts” (1132). But note how that stanza begins: Vespasian’s likened to a “wild boar.” The Roman standard is a dragon (394-96), another animal, and they fight elsewhere “like griffons” (556). It’s just not necessarily bad to be “animalized.” After all, medieval heraldry did it all the time. England’s King Richard I was “lion-hearted.”

What’s happening in this stanza, rather, is a double recognition, or, if you will, a double misrecognition, doubled by its performance for the poem’s audience: Vespasian, like his readers, recognizes his enemies as just human enough to make that humanity something worth taking from them. There’s no point in animalizing something that’s already known to be animal. The violence of the act requires that first recognition — what we must call a kind of “identification” or even “sympathy” — that must then be waylaid in a direction we generally don’t expect identification and sympathy to go. Humanization here is no salvation; it’s the prelude to further acts of violence, a recognition followed by the cruelty of deliberate misrecognition. The pleasures of such violence are among, even chief among, those this poem offers.

I’m so skeptical about the conjunction of “humanization” and kindness, and the notion that all forms of “humanization” should be welcomed. Some forms of violence and domination do indeed treat people as objects, as vermin, or as livestock; while some “ungrievable life,” to use Judith Butler’s formulation,[3] is treated as just human enough for others to be made to bear the responsibility for their own death, or for others to exult in their deaths, or indeed to exult precisely in the reduction of a human to an object. The sadist gets off by maltreating a human, not a rock. Resisting violence and cruelty simply must require a more convincing practice than “humanization.” If there’s some magic concept that can put a stop to all this, I wish I knew it: but this one isn’t it.

Thank you.

- For this talk, I looked at Marco Nievergelt, “The Sege of Melayne and the Siege of Jerusalem: National Identity, Beleaguered Christendom, and Holy War during the Great Papal Schism,” The Chaucer Review 49, no. 4 (2015): 402–26; Patricia A. DeMarco, “Cultural Trauma and Christian Identity in the Late Medieval Heroic Epic, The Siege of Jerusalem,” Literature and Medicine 33, no. 2 (2015): 279–301; Vanita Neelakanta, Retelling the Siege of Jerusalem in Early Modern England (University of Delaware Press, 2019); Mo Pareles, “Cannibal Maria in the Siege of Jerusalem: New Approaches,” Religion Compass 17, no. 12 (2023): 1–10. Nievergelt quotes Christine Chism (“By continually soliciting sympathy for its victims, the poem underscores their humanity and threatens its initial paradigm”), and cites Conklin Akbari, Narin van Court, and Yeager as well as evidence of the poem’s “complex and ambivalent representation of the Jews,” and effectively endorses their work by further illustrating how “indeed, the Jews are not only humanized, but individualized” (418). Although DeMarco goes too far in the other direction, I think, in emphasizing how the poem “imped[es]…compassionate identification” (288), she still misses the pleasure offered by the poem’s sadism. Likewise for Neelekanta’s tracing of shifts in identification in medieval to early modern responses to the siege from the Romans to the beleaguered Jews: entangled identification was already operating in the Middle English Siege. Parales’s reading of the poetic tradition (which contrasts one strain to another, based in the Hebrew Sefer Yosippon) is far more promising than what I know of the critical tradition to date. My question is the degree to which the poem holds Maria to be responsible for the death of her own child because she belongs to a besieged people. My sense from encountering such reactions in the present day is that sympathy and horror readily mix with contempt and condemnation, and that all such responses necessarily entail “identification” and “humanization.” At the moment I have in mind Feroze Sidhwa “65 Doctors, Nurses and Paramedics: What We Saw in Gaza” (NY Times Oct 9 2024); Yaniv Kubovich, “No Civilians. Everyone’s a Terrorist’: IDF Soldiers Expose Arbitrary Killings and Rampant Lawlessness in Gaza’s Netzarim Corridor” (Haaretz Dec 18 2024).↑

- Translation from The Siege of Jerusalem: A Broadview Anthology of British Literature Edition, trans. Adrienne Williams Boyarin (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2013). ↑

- Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (New York: Verso, 2004); Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009). ↑