Sewanee 2025: Response to “Bodies and Being in the World” (Session 33)

Hi everyone.

Caitlin Kelly’s paper reads Chaucer, especially, through the lens of veganism. There’s a lot to take on, and I’m happy to offer my own contribution. Long ago, I once intended to write a dissertation called “eating and not eating meat in the Middle Ages,” so I have a lot of material on hand. Let me offer just a little.

I was thinking, first of all, about the relation of the imagined metropole and imagined present to meat-eating. On the one hand, we have primordial vegetarianism: Genesis, up to chapter 9, after the Flood, or the Golden Age, or the Gymnosophists and Brahmans legendarily encountered by Alexander the Great; on the other, the excessive or monstrous carnivorousness of the Scots in the Own and the Nightingale, or the Irish who have never heard of bread in Gerald’s Topographia, or, of course, the phantasmagoric Mongols in any number of thirteenth-century Latin histories.

Closer to home: when the thirteenth-century natural scientist Aldobrandino of Siena observed that “among all the things that provide man with his nutrition, meat provides him with the most. It fattens him and gives him strength,”[1] he reaffirmed evidence that he could have drawn from any well sunk in the common field of medieval warrior literature. A vita of Columba of Iona, for instance, tells of the saint’s asking a reaper what he had eaten in his former profession: “When I was a warrior,” he says, “I used to consume a fat ox to my full meal:’” the saint tells him to do just that, and he does, and then Columbia reënfleshes the bones, and then donates the ox to the other reapers, uncertainly for food or for labor.[2] The Carolingians, we’re told, admired voracious meat-eating: Charlemagne praised Adelchis, son of the king of the Lombards, for just that, while the Italian nobleman Wido of Tuscany was disqualified from the Frankish throne for, in part, for providing an excessively frugal feast.3] Einhard reports Charlemagne’s irritation at his doctors when they compelled him to give up roast meat, while, centuries later, the Middle English Alphabet of Tales tells us that the emperor “ate but little bread, but all at once he would eat a quarter of a sheep, or two hens, or a goose, or a pig’s shoulder, a peacock, a crane, or a whole hare.”[4] We have, too, in the Chanson de Guillaume, a hero, who, after a setback in battle, scarfs down a loaf of bread, two roast pasties, and whole pork brawn, and then an entire peacock. Then his wife upbraids him for his lassitude, for no one who could eat like that should think themselves incapable of war.[5] All these men – crucially men, I think – show their secular power over other people – other bodies – through these enormous, fleshy appetites, the very figure of their political domination. Simple enough.

Is the abstinent diet that divergent from this though? From the perspective of animals, certainly: surely it’s better for them not to be killed and eaten. But the ascetic’s standpoint is also one of domination. The ascetic does battle with the world, the devil, and the flesh. They dominate their lower selves, controlling their own flesh and their animal appetites. Asceticism is a practice of internal domestication. The actions are, crucially, different from those of the warriors, but the values strike me as not dissimilar. We might talk about that further.

One last point, on Margery Kempe. When she gives up meat, she’s told to “forsake that which you love best in this world.” She’s exchanging one pleasure for another, the social elevation that attends her auto-sanctification, since when Jesus tells her to start eating meat again, she above all dreads social humiliation. And I’ve long been fascinated by what happens in the manuscript at this point. The “red-ink annotator,” willing to delete or even rewrite passages to suit his doctrinal preferences, leaves the margin blank when Kempe first stops eating meat, but when she takes it up again, at folio 78v, he writes ‘fleysche’ near the passage, and draws a box around it: it may be too much to suggest that he was disturbed by this change in Kempe’s religious practices, but this Carthusian – a Carthusian, critically, a notoriously abstinent order – certainly found her new divergence from his own vows remarkable. He also thought medieval meat was worth talking about, and I expect you’ll join him in that.

Melissa Heide’s paper on “The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle” reads the Dame in terms of her disruptiveness: this (mainly) loathsome lady hits the court like an ecological thunderbolt, repulsing everyone but Gawain, the one knight graceful enough to keep his composure. And good for him, because he’s the one certain winner in all this – a good subject, a good knight, eventually a good husband, and perhaps best of all, he gets to keep the land whose contested ownership led to this whole mess in the first place.

This was, I think, my first time reading this romance, or my first time in a good long while. I was struck by its several divergences from the standard “loathly lady” plot, and the divergences in Ragnelle’s portrait from other medieval hideous women. At the turn of the last century, Howard Maynadier’s Harvard dissertation gathered a host of loathly ladies, from French, Old Norse, German, and especially Celtic sources[6] – in them, as you surely know, a young man shares a bed, a kiss, or sex with a hideous woman, in witting or otherwise exchange for kingship; not long after, Roger Sherman Loomis found in the story traces of the myth of the marriage of sun (Gawain) to land (the lady);[7] and, in 1945 in Speculum, Ananda Coomaraswamy, in a late article in his breathtakingly prolific career, traced the motif across Eurasia to Indian cosmology, and, naturally, to the very metaphysics of the self.[8]

All that may be true enough, but what we have here is this romance, surviving in a single late medieval manuscript, and I want to observe, first, what here doesn’t match the old sovereignty pattern. Gawain already has his land. He’s also not the sovereign: Arthur is. Gawain has his land from Arthur, no kissing required. And Ragnelle doesn’t offer sovereignty; she wants to be recognized as wanting it. She wants her desires to be taken seriously.

More than with the Wife of Bath’s old woman, we can ask if what Ragnelle wants is what women want in general, or whether she’s universalizing her own quite particular desire: after all, we know she and her brother are locked in a contest over land, and her marriage to Gawain both frees her from her step-mother’s machinations and cuts the knees out from under any counter-claim.[9] That’s her problem, though, not women’s in general. As for the sovereignty Ragnelle enjoys, interpersonally, it’s that of a good marriage, companionship that is, not at all dissimilar to the mutual responsibility Arthur and Gawain share with each other. This is not so much a “sovereign exception,” then, as it is contractual, negotiated mutual obligations – and here I have in mind Peggy McCracken’s words on medieval sovereignty in her In the Skin of a Beast.[10] Marital sovereignty is not distinct from but rather the very image of the pacific and mutually sacrificing political sovereignty this romance favors.[11]

Furthermore, while Heide, like others, finds much of the animal in Ragnelle when she’s in her cursed state, I’m struck by her only glancing or suggested beastliness. Now, we do know a lot more about her looks than the old woman of Wife of Bath’s Tale: “a fouler wight there may no man devyse,” and that’s it for her. As for Ragnelle, she does have boar’s tusks, and she’s called a “sow”: that’s incontrovertible. But the poem could have gone so much further. In Chrétien’s Conte du graal, the hideous lady –christened Cundrie in the German adaptations – has eye sockets not larger than a rat’s, a nose like a monkey’s or a cat’s, the lips of a donkey or cow, and a beard like a he-goat.[12] John Lydgate’s satirical portrait “Whan she hath on hire hood of greene” features a woman with a hair as stiff as a pig’s bristles, a belly like a cow’s, bearded, again, like a goat, skin as tender as a hake’s,[13] and limbs as long and gangly as an elephant’s.[14] And I’ll do no more than gesture towards the animal imagery of William Dunbar’s exceptionally nasty racist poem of 1505ish. Ragnelle isn’t necessarily animal, and therefore not necessarily ecological. In 2011, Sandy Feinstein proposed, and then stepped away from, efforts to read Ragnelle as a figure of hideous old age: so she’s not quite that, either.[15] What she is, of course, is a figure of excess, a body and appetite out of bounds, and if following a pattern, the pattern of the misogynist antiblazon traced so well back in 1984 in Jan Ziolkowski’s “Avatars of Ugliness”:[16] in Mary Douglas’s old formation, Ragnelle is dirt, because she’s matter out of place. Is this filth an ecological image? An animal one? Or is it filth like the filth of the fertile feminized body we find in The Misery of the Human Condition? Or is it still more disorganized. Think of the psychoanalytic Real of Lacan via Zizek: that’s straightforward, and you do the math on that; or think of primordial matter, the hyle, in, for example, Bernard Silvestris’s Cosmographia, which is prenatural, prior to kind. What is matter before it has nature, or before nature has it?

And at last: Jessica Hines considers how the extreme cold of Robert Henryson’s childhood might have been carried forward into one of his chief poetic interests. I think, for example, of the opening of the Testament of Cresseid, which opens in Aries, in Mid-Lent – the far edge of Winter, or not, if you’re in Scotland – when “Schouris of haill gart fra the north discend.” In a larger sense, I’m wondering whether poets who aren’t Scottish, and who had a similarly freezing youth contemporary with Henryson also found themselves resorting to wintery scenes often in their poetic maturity. Was later fifteenth-century English poetry generally prone to chilliness?

Hines’ particular interest is in Henryson’s moral weighing of varying needs – the birds vs the fowler in the barrenness of winter – which is itself, I would wager, part of her larger scholarly interest in the politics of pity, mercy, and compassion. What’s striking to me, though, is Henryson’s role as a witness.

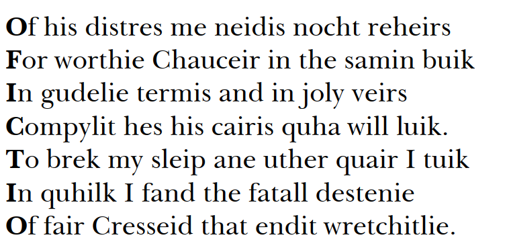

He’s not uninterested in that kind of meta-representational presence. It might be something he picked up from Chaucer. Consider, for example, this stanza from the Testament: it describes an old man taking down a book to keep himself company by his fire, not Chaucer’s Troilus, but another book, the one you’re about to hear. A 1994 article by William Stephenson alerted me to the acrostic, which, if you hadn’t seen it before, I trust you do now: O FICTIO.[17]

Now, he’s being clever here: he’s playing, I wager, on the parasitic relationship of fiction on what passes for history, as well as playing on the desire of this old, impotent, and somewhat frozen man to tell a story where Cresseid suffers. This isn’t so much a story about what Cresseid undergoes as it is about the kind of fiction such a man would produce.

Henryson’s fables do something different though. The genre is a retentive one, telling stories that were already ancient by the time Henryson tried his hand at them. As this Dunfirmline schoolmaster knew better than most, they were a schoolroom genre, suitable for teaching rhetorical compression and amplification. The prologues and epimythia of Henryson’s fables attest to his especial skill in the latter. All that, though, is typical of the genre: the plots stay the same, the words and moralizations change.

Except in two, he includes himself as a character. “The Lion and the Mouse” begins with a dream vision, where Henryson is visited by an Aesop elevated into the position of otherworldly sage, who allows himself to be cajoled into telling a story. The next fable, “The Preaching of the Swallow,” refines this even further, as here we have Henryson himself seeing the swallow preach, and the foolish birds’ mockery, three times. And then comes the killing.

Henryson’s fable anticipates Martin Luther’s 1534 letter to his servant Wolfgang Sieberger: to warn Sieberger against the frivolity of trapping birds, Luther wrote a short legal complaint in the birds’ collective voice, outraged that Sieberger has deprived them of “the liberty of flying in the air and picking up grains of corn.”[18] Luther’s letter, however, is but a slightly imperious thwarting of his servant’s enjoyments, with little concern for the birds themselves. Henryson’s work by contrast is a catastrophe, watched in horror by the poet himself, within the fable rather than invisibly without. No distant judge, no mere schoolmaster, Henryson’s stand-in is as helpless a witness to what befalls the birds as is the swallow. He and this tiny, wise bird alike know what awaits the others, and as much as the foolish birds got what they should have expected, seeing them killed a “rycht grit hertis sair to se.”

That heart soreness hits not because the birds are “humanized” or because the narrator is “avanized”, but because the fable recognizes a shared feeling of exposure to the elements: as we have heard, birds and narrator alike go through the year, experiencing what it brings. And what matters too is a recognized feeling of shared vulnerability, common to everything that lives and cares about its life. It is on this basis that the fable appeals to us. Language here is not a technology that separates human from animal, but rather a medium of communion, recognition, and community.[19] As I do so often, I have in mind here Derrida’s words on the “nonpower at the heart of power” in his discussion of Bentham in the first chapter of The Animal that Therefore I am….

Thanks for listening; thanks for having me; I’m looking forward to our conversation.

- Quoted in Massimo Montanari, “Peasants, Warriors, and Priests: Images of Society and Styles of Diet,” in Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present, ed. Montanari and Jean Louis Flandrin (Columbia UP, 1999), 179. ↑

- Cited in Dorothy Ann Bray, A List of Motifs in the Lives of the Early Irish Saints (Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1992), 179. See the Life of Colomb Cille in Lives of Saints, from the Book of Lismore, ed. and trans. Whitley Stokes (Clarendon, 1890), 179. The reaper is Mael Uma son of Baetán, who the Annals of Tigernach reports as having defeated Eanfraith, brother of Aethelferth.↑

- Montanari, The Culture of Food (Blackwell, 1994), 22-23. Liutprand, Antapodosis [Retribution] I.16, in The Complete Works of Liudprand of Cremona, Paolo Squatriti trans. (Catholic UP, 2007), 58-59. ↑

- Einhard, in Two Lives of Charlemagne, Lewis Thorpe trans. (Penguin, 1969), III.22, 77. Mary Macloed Banks, ed. An Alphabet of Tales. An English 15th-Century Translation of the Alphabetum Narrationum (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1905), “De statura et vita Karoli regis,” CCCCXXII, 290. ↑

- La chanson de Guillaume and La prise d’Orange, ed. and trans. Philip E. Bennett (Grant & Cutler, 2000), ll. 1053-59 and ll. 1422-32. ↑

- The Wife of Bath’s Tale: its sources and analogues (David Nutt, 1901) ↑

- Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance (Columbia UP, 1926) ↑

- “On the Loathly Bride” Speculum 20.4 (1945): 391-404. ↑

- My immediate sense is that, as learned as it is, Sheryl L. Forste-Grupp’s “A Woman Circumvents the Laws of Primogeniture in ‘The Weddynge of Sir Gawen and Dame Ragnell,’” Studies in Philology 99.2 (2002): 105-22 cares a lot more about the specifics of late medieval land law than the writer of the poem did. ↑

- In the Skin of a Beast: Sovereignty and Animality in Medieval France (U Chicago P, 2017). ↑

- Manuel Aguirre, “The Riddle of Sovereignty,” The Modern Language Review 88.2 (1993): 273–82, by contrast, reads the narrative as distributing the land sovereignty theme to Arthur/Gromer and the marital sovereignty theme to Gawain/Ragnelle, and the Stepmother the hostile manifestation of Ragnelle herself. He sees the marital and political sovereignty themes as distinct, whereas I see them as interrelated: Ragnelle realizes this much more explicitly than the Wife of Bath’s Tale, where it is no more than implied. Helena Znojemská, “Loathly Ladies’ Lessons: Negotiating Structures of Gender in ‘The Tale of Florent,’ ‘The Wife of Bath’s Tale,’ and ‘The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnell,” Acta Universitatis Carolinae Philologica 2 (2022): 21-37 is a prod to take the ending more seriously (viz, Gawain’s uxoriousness, and Ragnelle’s quickish death). ↑

- vv. 4556-62, Charles Méla ed. from Berne 354. ↑

- Merluccius merluccius, also known as the “Cornish salmon.” ↑

- In James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, ed, A Selection from the Minor Poems of Dan John Lydgate (1840). ↑

- “Longevity and Loathly Ladies in Three Medieval Romances,” Arthuriana 21.3 (2011): 23-48. John Brugge’s “Fertility Myth and Female Sovereignty in ‘The Weddynge of Sir Gawen and Dame Ragnell’ Chaucer Review 39.2 (2004): 198-218 should, sadly, be avoided. ↑

- Modern Language Review 79.1 (1984): 1-20; see also Paul Salmon, “The Wild Man in “Iwein” and Medieval Descriptive Technique,” The Modern Language Review 56.4 (1061): 520-28. Cf. Matthew of Vendôme Ars Versificatoria, item 58, the description of the hideous woman Beroe, who is more deliquescent than animalized (trans Roger P. Parr, Marquette UP, 1981) ↑

- “The Acrostic ‘Fictio’ in Robert Henryson’s The Testament of Cresseid (Lines 58-63).” The Chaucer Review 29 (1994): 163-65 ↑

- The Letters of Martin Luther. Ed. and Trans. Margaret A. Currie (Macmillan, 1908), 300-301. ↑

- I adapt these last paragraphs from my “Huntings of the Hare: The Medieval and Early Modern Poetry of Imperiled Animals,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Animals and Literature , ed. Susan McHugh, Robert McKay, and John Miller (Palgrave MacMillan, 2018). ↑