The Boar’s Head Carol: No Oxford Student ever strangled a pig with his Aristotle.

On Dec 23 of this year, the Burgon Society, founded in 2000 and devoted to the study of academic regalia, posted to Twitter, a microblogging website, a double claim about the Boar’s Head Ceremony of Queen’s College, Oxford: that this ceremony – in which a boar’s head or a simulacrum thereof is brought out to serve as the centerpiece of a Christmas feast – dates to the 1340s, and that it originates “after a student going to church on Christmas Eve was threatened by a wild boar.”

The latter claim is an obvious just-so story. My Christmas gift to myself was spending the day researching and writing the following. Here’s what I turned up:

Various witnesses report the story with varying degrees of credulity, some as fact, some as tradition, some as just a story, many of them seeming to invent details on the fly, as is suitable for a folk tale. We find it in J. John’s Christmas Compendium (Continuum Books, 2005) where the student is a “Mr Copcot” walking in “Shotover Forest,” when he’s attacked by a wild boar: unable to draw his sword in time, he has to save himself by ramming his copy of Aristotle into its mouth (11). In 1846’s Wanderings of a Pen and Pencil by Francis Paul Palmer and Alfred Henry Forrester, despite carrying a spear (287), he still book-chokes the boar. The boar’s head feast, as we’re told in Sophie Jackson’s The Medieval Christmas (History Press, 2013), and nearly everywhere else, was given in his honor. And, depressingly, we find the story recited with wide-eyed innocence in books offered by University Publishers: William E. Studwell, The Christmas Carol Reader (The Haworth Press, 1995; rpnt, 2011, Routledge, 140) and Jeffrey Greene’s The Golden-Bristled Boar: Last Ferocious Beast of the Forest (University of Virginia Press, 2011, 21).

Paul Sullivan’s 2012 Little Book of Oxfordshire (History Press, yet again) gives the student a first name, John, dates him to the fifteenth (rather than fourteenth) century, and associates the student with both Queen’s College and nearby town of Horspath, whose church of St Giles has a “seventeenth-century stained glass” showing the student “stuffing a book into the mouth of a wild boar.” Sullivan repeats the story in his 2013 The Secret History of Oxford (History Press!), with the slightly more delicate “putting a book into the mouth of a wild boar.”

Reaktion Book’s animal series’ volume on The Wild Boar, written by the former medievalist Dorothy Yamamoto, could have been more suspicious: “whether anything like this happened is impossible to say”: no, absolutely not, it did not happen. Yamamoto does, however, usefully point out that the College’s eighteenth-century painted portrait supposed to be of the student Copcot “shows a gray-bearded patriarch in flowing robes … and is in fact a close copy of a stained-glass window in Horspath parish church, a few miles away.” The student’s surname must come from this painting, or the window, as each bear below them the word “Copcot.”

One Karl Blind –a German revolutionary exiled in England, and author of Yggdrasil, or, The Teutonic Tree of Existence – somewhat deliriously calls the name Copcot a “mystic inscription” ( “The Boar’s Head Dinner at Oxford and a Germanic Sun-God,” The Gentleman’s Magazine January 1877, 97, in German in the Neue Monatshefte für Dichtkunst und Kritik, the same year, as “”Der altgermanische Sonnendienst in England” 156 (“die mystische Inschrift”). James J Moore, 1878’s Historical Handbook and Guide to Oxford (186) rips off most of Blind word for word, while Peter Hampton Ditchfield’s 1896 Old English Customs Extant at the Present Time spells this name as “Cop Cot” (24), without supposing any mystic meaning.

What Hampton and Blind get right (as does Moore through Blind, feloniously) and what Sullivan doesn’t, and Yamamoto omits, is that neither the Copcot glass and nor the Copcot painting show the saint (?) stuffing a book into a boar’s mouth. Both have the saint (?) instead holding a book in his left hand, and in his right, a lance erect, on whose top is a boar’s head, transfixed. The painting (reproduced online only here), dates to c. 1754, while the window in Horspath Church dates not to the fifteenth century (contra Sullivan), but rather (and quite obviously, once you’ve seen it) to the eighteenth century or thereabouts: to 1740, supposedly. It’s said to be by William Price the younger, the third of three generations of English glass painters (for more on this family, see a 1953 article in The Antiquaries Journal, which I don’t have access to at present). That is, the window might not even be, technically speaking, “stained glass.” If the window – as it’s said – was a gift of Magdalen College, then it’s connection to a Queen’s College ceremony seems even more unlikely.

Furthermore, August A. Imholtz’s short article (The Classical Outlook 59.2 (1982): 68-69) on the origins of the phrase “it’s Greek to me” usefully prints a letter of 6 Sept 1980 by Helen Powell, Assistant Librarian at Queen’s College, Oxford, affirming that no Copcot, John or otherwise, “is known to have been a member of the University in the 15th century, or indeed at any other time.” It’s not that Copcots have never existed: a John Copcot was associated with Cambridge – not Oxford — in the time of the playwright and spy Christopher Marlowe, while the Copcots were a family of some importance in the centuries prior to the eighteenth in the region. But this window’s Copcot could not have been a Queen’s College Copcot.

I’ve dispelled falsehoods but found no real answers: it remains a mystery why a window bearing the name Copcot, depicting a saint (?) with a boar’s head impaled on a lance, should have been installed in a Horspath’s Church of Saint Giles, and why this painting should have been copied and displayed at nearby Queen’s College, Oxford. Sullivan is wrong, presumably because he never bothered to look at the window; Blind is wrong, because of his mystical suppositions; and the assertion that the window illustrates the legend is wrong, because the old man bearing book and the lance strikes me, as it did Yamamoto, as rather too old to represent a student.

To follow the trail to what should be its head: in 1899, William S. Walsh’s Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities calls the story a “local legend” (133), while W. M. Wade, in his 1817 Walks in Oxford, ascribes the story to Tradition (as does John Walker’s 1806 Oxoniana (53)), without naming the student, and quotes from some unnamed source that he “rammed in the volume and cried, Graecum est,” which he then ties off with this moral: “fairly choking the savage with the sage” (167 n1). The Latin — a kind of James Bond-level killing joke — is a frequent reference in the later 19th century, appearing in, for example, William Wallace Fyfe’s 1860 Christmas: Its Customs and Carols, Edward Francis Rimbault’s 1865 Old English Carols, and Nathan Boughton Warren’s 1868 The Holidays: Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide, where he’s able to tell a joke about a “boar” slain by a “bore,” that is Aristotle, and where he suggests – I think this is meant to be a joke, too – that the student’s surname must be Bacon, hence the rise of Baconianism at Oxford. J. P. McCaskey’s compilation book, Christmas in Song, Sketch, and Story (1891, New York) is admirably suspicious, as it points out that the Christmas day boar’s head ceremony is also observed at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and the Inner Temple, London: surely our student, whatever his name and dates, can’t have brandished his boar-killing book so often (288).

Of course, no fourteenth-century Oxford student would have been reading Aristotle in Greek.

And now for the (almost) origin: the 1794 History of the County of Cumberland by William Hutchinson is the first not just to quote but to actually cite a song about the episode from The Oxford Sausage by “Dr. Harrington of Bath” (293). Henry Harington, physician, composer, and, briefly, Bath’s mayor, is nowhere else to my knowledge named as the Sausage’s composer or lyricist: but I’d prefer to believe he’s responsible, because Hutchinson could have known him. The Oxford Sausage, from 1764, is the earliest written witness to the story (85-86) of the student, the boar, the book, and the “graecum est.” The longer we get from the Sausage, the more likely the writer is to swallow it whole. Sorry.

Even so, there’s a still earlier version: John Pointer’s 1749 Oxoniensis Academia: Or, The Antiquities and Curiosities of the University of Oxford (39), which uses virtually the same language as 1744’s A Pocket Companion for Oxford (40): in both, however, we have nothing but a student killing a wild boar in Shotover Wood, weapon unspecified, without reference to Aristotle or the student’s name. Here is the Pocket Companion:

a Boar’s Head on Christmas Day, usher’d in very solemly with a celebrated Monkish Song, in Memory of a Taberdar‘s killing a wild Boar in Shotover Wood.

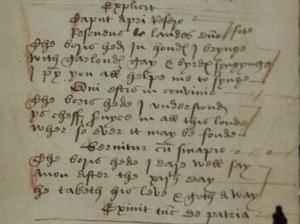

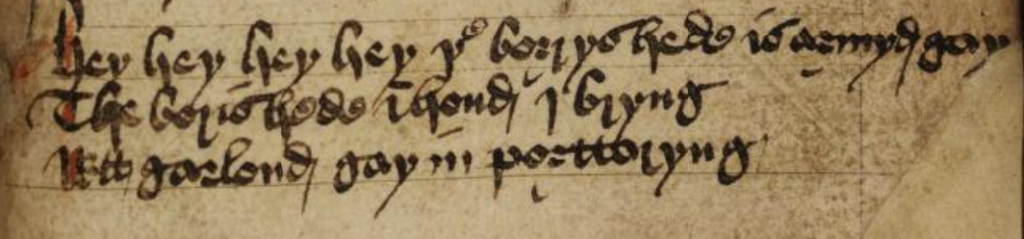

And that’s it. I’ve found nothing earlier: nothing from the seventeenth century at all, nothing in EEBO, nothing in various JSTOR searches and the like: for now, this is where we stop. The “monkish” song is the boar’s head carol: you can find it in various versions in Cambridge UK, St John’s College S.54 (259) (f. 1); Oxford, Balliol College 354, 477 – and in print in Wynken de Worde’s 1521 Christmasse Carolles; in British Library Addit. 5665, ff. 7v-8, the “Ritson Manuscript,” and in Brogyntyn MS ii.1, f. 202 (formally, and aptly, called the Porkington Manuscript).

If the Horspath glass dates to 1740, then it predates very slightly the Pocket Companion. I’m imagining that this mysterious – not mystical –glass may have been gathered into the Pocket Companion’s story, which was then gathered up by John Pointer, which was then turned into lively song in the student days of Dr. Harrington of Bath, and from thence it ramified through a host of writers, incredulous and sadly otherwise.

I’d love to know more about the painted glass. Do let me know what you know.