From The Forbidden Experiment to Little Communities

Further Sabbatical Fruits – the first third of what’s bound to be the longest chapter of Book 2, Chapter 2, On Isolated and Feral Children. Thanks to Maryam Razaz and St Chad’s, Durham University, and also to Anna Klosowska in Dijon for letting me present this material (in two separate chunks, mercifully) in June 2017.

Earlier versions are here and here, or, what began as accidentally falling down an irrelevant research hole became, knock on wood, something that’s going to be, um, ‘real.’

A group of children, confined to a house, never taught to speak; an infant, certain to grow up to supplant the king, exposed and left for dead, only to be rescued by a mothering wolf; an abandoned child, raised imperfectly by animals, unwilling or unable to adapt to the expectations of human culture: stories like these, of children deprived of—or preserved from—human nurturing and cultural training have typically been thought to say something about what it means to be a truly human, truly sovereign, or even to be confirmations of the superiority of an ethnos or faith. They are, in other words, taken as stories of isolation, and therefore as stories of truth, as if the truth is the thing that emerges only when all the merely secondary things have been refined away.

This chapter argues that these stories are better understood not as about isolation, but about community, sometimes failed, sometimes present, and ultimately, in my treatment of the Wolf Child of Hesse, a choice that makes one group at the expense of another. Normative notions of what the human should be make these stories speak predictable lessons about the opposition between spoken language and irrationality, nature and culture, and even care and violence. But this material does not quite take the human for granted. They pose it as a question, and in the space opened by that question, we have the chance to answer it otherwise.

From The Forbidden Experiment to Little Communities

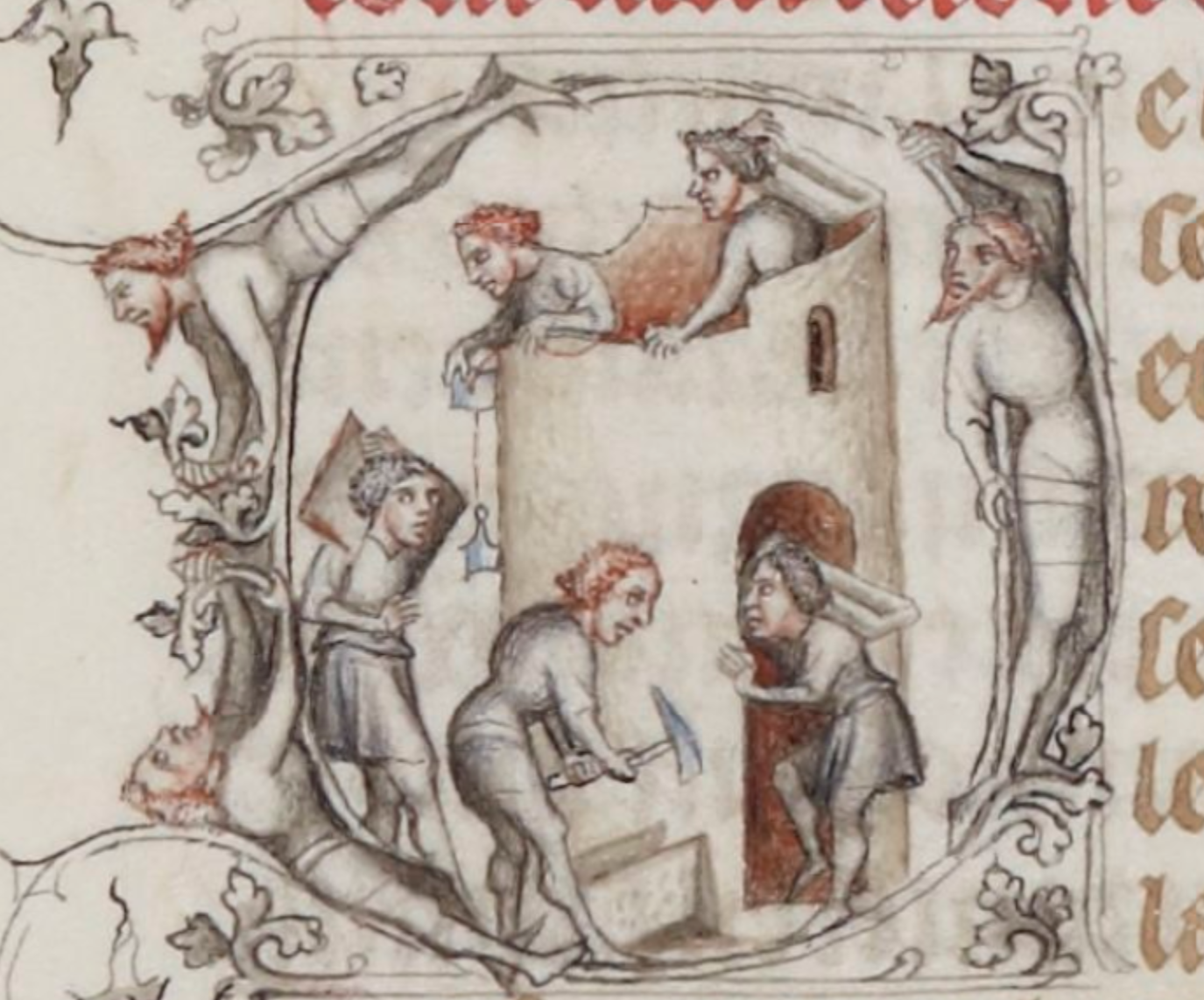

In the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9), the “children of Adam” decide to erect a tower to “reach to heaven” to “make our name famous before we be scattered abroad into all lands.” This is a story about the architectural possibilities brick opens up over stone (11:3); about collective rather than regal politics, as later commentators, not scripture itself, lay the responsibility for Babel Tower on the tyrant Nimrod;[1] and yet another Genesiac story about God’s jealous destruction of human felicity.[2] Most famously, it is about the catastrophic origins of linguistic diversity, and therefore yet another tantalizing account of the irretrievable loss of a first, happy unity.[3] At times studious indifference characterizes speculations about the language God used to create the world in Genesis’ first creation story and Adam to name the animals in the second: Augustine sometimes does no more than allow that the language of Adam and Eve, whatever it might have been, might have survived to the present, but he insisted that it was but a sop to human limitations to imagine that God “spoke” in language.[4] Those many commentators less reluctant to settle on a language tended to chose Hebrew.[5] The Book of Jubilees, a second-century BCE retelling of Genesis, is one of the earliest witnesses of this tendency, when it has God teach Abraham this “revealed language,” the lost “language of the creation,” once shared with “the animals, the cattle, the birds, everything that walks and everything that moves”;[6] when the Syriac Cave of Treasures—a Christian universal history begun as early as the third century and finalized by the sixth—advocates for Syriac, its sneering reference to the “ignorant mistake” of those who believe the first language to be Hebrew is itself evidence for how common this identification must have been already.[7] Key early Christian advocates for Hebrew include Isidore of Seville and Bede, and even Augustine, in his City of God;[8] the eighth-century commentator Alcuin of York explains why: to realize the typically neat symmetry of medieval exegesis, Alcuin writes that it was suitable (oportuit) that Christ’s salvific language, which he supposed to be Hebrew, should also be the language through which death first entered the world.[9]

In a letter protesting her own monastery’s excommunication, the twelfth-century abbess Hildegard of Bingen proposed that the first language was not speech but angelic musical harmony, in whose glory Adam shared until he sinned, which is why her nuns should be allowed again to sing their services.[10] With Hildegard’s longing to participate in the first “divine melody”; with Jubilees and its angelic language; with the generally “numinous character” imparted to Hebrew in speculations on Babel and Eden;[11] and, for that matter, with the “Evernew Tongue” of a ninth- or tenth-century Irish visionary hexameron, the Tenga Bithnua, which will also be understood by the “sea-creatures and beasts and cattle and birds and serpents and demons, which all will speak at the Judgment”[12]: in all of this, we witness the two main motives driving attempts to identify the first language. The first is to find a language before a diversity of tongues to get at language’s truth, led by the still-common assumption that singular things are truer or at least better than heterogenous ones. The second motive is to arrive at that great unity, God Himself, through his own language, which must be a language, like Hebrew, that persists into the present day, just as God himself does.[13] The original language becomes key to burrowing under the wreck of the present, to emerge once again in paradise, or in the time of the Last Judgment and the coming glory. With this, language’s inadequacy can be cured of its seemingly irreducible confusion, and we can know it as the voice of our truth.

The first record of an experimental attempt to find such a language and such a foundation dates to the fifth century BCE, from Herodotus’s story of Psamtik (whom Herodotus calls Psammetichus), a powerful and long-ruling Pharaoh of the twenty-sixth dynasty. Though the Egyptians reputed themselves to be the “oldest nation on earth,” others argued that the honor belonged to the Phrygians: as Psamtik wanted experimental confirmation, he had children raised in isolation with a herdsman who was never to speak to them, with the expectation that, freed from educational meddling, they would produce the primordial language, spontaneously. After two years — and as the first Englishing of Herodotus runs — “both the little brats, sprawling at his feete, and stretching forth their handds, cryed thus: Beccos, Beccos,”[14] which Psamtik and his advisers understood as the Phrygian word for bread. Thus he had the unpleasant surprise of learning that not the Egyptians, but the Phrygians, were the oldest culture. Later commentators have tended to misunderstand the story’s punchline: it is less about the first language than the first people.[15] What Psamtik wanted was not a general principle of the origin of language, but a miraculous, and therefore extracultural foundation for his claims to cultural superiority.

Medieval Latin Christendom could have heard only faint report of this story. Herodotus would not be translated into Latin until the later fifteenth century, while his Psamtik story slides into European vernaculars only with the widely popular Silva de varia leccíon of the sixteenth-century Sevillan humanist Pedro Mexía, itself quickly translated into French and English,[16] and from thence into virtually uncountable paraphrases, for example, the discussion by the Montpellier physician Laurence Joubert (d. 1582) of linguistic origins and deafness.[17] As long ago as the first century of our era, Herodotus already tended to be cited, by Cicero among others, only through intermediaries.[18] The story itself may still have circulated independently. Aristophanes uses it in his Clouds to form an insult about “moon-bread” children, suggesting he trusted his audience to get the joke. The first-century Roman rhetorician Quintillian tells what may be an independent, or garbled, version, in which not one but several princes conduct the experiment.[19] In the version told in the Exhortation to the Greeks (the Protrepticus) by the early Christian theologian Clement of Alexandria (d. 215), it is not a herdsmen but goats that raise the children, a strange misreading of the original that would be reproduced in commentaries on Aristophanes at least as late as the tenth century.[20] But Quintilian sustained little regular readership in medieval Latinity,[21] while Clement’s Protepticus, a rare work even in its original Greek, would not be translated into Latin until 1551.[22] Clement’s contemporary Tertullian also tells the story in his To the Heathens (Ad nationes), drawing on a version Herodotus rejected, in which not a herdsman but a nurse with an amputated tongue nurtures the children: her injury is sufficient for Tertullian to dismiss the story, as no one could survive the removal of “that vital instrument of the soul.”[23] Just one medieval manuscript of this last work survives, a ninth-century copy used by the notorious polemicist Agobard of Lyons,[24] and I have encountered no medieval quotation of or even allusion to Tertullian’s retelling of the story. Ad nationes would not appear again until 1625, well after Herodotus and Psamtik made their way back into European writing.[25]

The next version of the experiment appears an astonishing 1700 years after Herodotus, in the thirteenth-century chronicle of the Franciscan historian Salimbene di Adam, who, several decades after the events he claims to be recording, explains that Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, wanted to know what language children would spontaneously produce if they were never spoken to, or even “blandirentur” [dandled].[26] As thirteenth-century Sicily was a particularly language-rich environment, Salimbene may have imagined Frederick conducting the experiment to establish a linguistic foundation for his rule in a place without any obvious cultural unity. He has the emperor wonder whether the spontaneous language would be Greek, Latin, or Arabic, or perhaps even their parental language, the kind that can be acquired without training, as if there were no originary language and as if one’s mother tongue were, so to speak, a genetic inheritance. What he learned instead is that without affection, without clapping and gestures and funny faces and babbling from their nurses, babies die [“non enim vivere possent sine aplausu et gestu et letitia faciei et blanditiis baiularum et nutricum suarum”].

Faint allusions also appear in a number of medieval Jewish writers, who take various stances on the experiment—Abraham Ibn Ezra (d. 1167) expects that a child raised in a desert with only a mute nurse would spontaneously produce Aramaic; Hillel of Verona expects the result to be Hebrew (d. c. 1295); Abraham Abulafia (d. 1291) and his contemporary Zerahyah ben Isaac ben Shealtiel Hen each doubt that any language would emerge, though both insist on Hebrew’s special character.[27] The Scottish historian Robert Lindsay (d. 1580) has his king King James IV conduct the experiment in 1493 with a mute woman housed with two children on Inchkeith, a barren island in the Firth of Forth. Lindsay concludes dubiously with “Sum sayis they spak goode hebrew bot as to my self I knaw not bot be the authoris reherse”;[28] he is writing late enough that his unnamed and uncited “authoris” may be Herodotus himself, or at least Pedro Mexía, with the Pharaoh garbed now in tartan.

Finally, the story is included in a great many records of the sixteenth-century court of the Mughal emperor Akbar, in chronicles kept in Persian and Arabic by both Akbar’s allies and enemies, and in Italian and Latin by Jesuit missionaries, whose letters and memoirs helped spread the story through European early modern and Enlightenment philosophical, medical, and travel writing. The anonymous continuation of the Akbarnama, the “Book of Akbar,” may be the only version that has any grounds to claim to be a first-hand account, although even this may well be just a local variant of the Herodotus story, transmitted to Akbar’s court by European travelers. To prove that speech comes from hearing, Akbar had several children raised by “tongue-tied” wetnurses, confined to a building that came to be called the “dumb house.” When Akbar visited the house in 1582, four years after the children were first interred, he heard “no cry…nor any speech…no talisman of speech, and nothing came out except the noise of the dumb.”[29] Much the same story would be told decades later, in the anonymous Dabestan-e Mazaheb (the “School of Religions), written between 1645 and 1658, whose surprising conclusion is that since “letters and language are not natural to man,” but only the result of instruction and conversation, the world must be “very ancient.”[30] The Arabic Selection of Chronicles by Bada’uni (d. 1605) has the version closest to those told by European writers. Bada’uni records Akbar’s astonished encounter with a man who can hear, despite having “no ears nor any trace of the orifice of the ear”: to test the origins of language, he has several infants locked up, with “well-disciplined” (rather than mute) nurses, who are commanded not to give the children “any instruction in speaking.” Then, without any transition or explanation, Bada’uni changes Akbar’s motivation: he now wants to determine which religious language the children would naturally produce, presumably Arabic, Hebrew, or Latin.[31] Roughly twenty children are locked up in what comes to be called the “dumb house,” and “three or four years” later, none can speak. Nothing more is said about the earless man.

Several early European accounts of Akbar’s court omit this story. Giovanni Battista Peruschi’s 1597 Informatio del regno, et stato del gran re di Mogor (published in Latin the following year, with additional material on Japan) limits itself to worrying whether Akbar could be an ally of Roman Catholicism,[32] while the True Relation without all Exception, of Strange and Admirable Accidents, which lately happened in the Kingdome of the Great Magor, from 1622, is little but an exoticizing indulgence in fantasies of absolute royal power: it devotes several of its thirteen pages to an often-told story of a problem-solving ape, which frolics among the Mughal courtiers and Akbar’s two hundred “boyes…which hee keepeth for unnaturall and beastly uses.”[33] Akbar’s forbidden experiment enters Europe via the letters of another Jesuit missionary, Jerome Xavier (d. 1617), who claims to have had the story from Akbar himself. Xavier explains that “nearly twenty years ago,” Akbar closed up “thirty children,” and “put guards over them so that the nurses might not teach them their language.” There is nothing about an earless man. Xavier instead only has Akbar conduct the experiment with an eye towards following “the laws and customs of the country whose language was that spoken by the children.” Since “none of the children came to speak distinctly,” Xavier calls the experiment a “failure”; for Akbar, it may have been something else, since it allowed him to justify following “no law but his own.”[34] Here Xavier presumably means the short-lived, syncretic faith of Dīn-i Ilāhī, designed by Akbar himself. With this, we have yet another story of Roman Catholics disappointed in their search for Prester John, the Asian or African king who might swoop in from “behind enemy lines” to crush Islam. Once Xavier introduced the story, other European writers would, so to speak, close the narrative loop, by telling it with Herodotus’s account.[35] Retellings often secularized the Akbar story, rendering it only about language origins rather than religion, so establishing the habit of modern critics to read the forbidden experiment as about anything but ethnos or religious creed.[36] Its inclusion in Daniel Sennert’s posthumously published medical manual, his Paralipomena, merits individual citation for its unexpected conclusion about parrots, which, as he explains, also can “never produce any human voice by their own will” (“nunquam sua sponte ullam humanam vocem proferunt”[37]) unless they are captured as chicks and taught to speak. By the later seventeenth century, Akbar’s experiment would be collected alongside stories of children raised by animals, like the sheep-boy of Ireland,[38] a mythic tradition I treat in the next two sections of this chapter.

Perhaps the strangest strain in modern discussions of these stories has been their credulity, especially given that Herodotus himself doubted the historical reality of at least some versions of the Psamtik tale. Modern scholars, however, sometimes take the trouble to quibble with Herodotus by insisting the experimental method seems more Egyptian than Greek, or vice versa, and that the word “Beccos” sounds more Egyptian than Phrygian. Professionals in early childhood development and linguistics, and even a few cultural historians, not infrequently dispute the validity of its design, sometimes after making a point of their skepticism over whether it happened. Others flaunt their conscience by condemning Psamtik’s cruelty. This is a very strange body of scholarship to read, not only because it misunderstands or forgets how early historiography works, but also because no one unpleasant enough to conduct these experiments could possibly be convinced by these arguments to abandon their vices.[39] Such errors of interpretation can be avoided simply by sorting the language experiment with the other, equally grandiose claims that clustered around all these potentates: Psamtik, for example, was reputed to be the inventor of the labyrinth,[40] while Salimbene frames his story with a set of what he calls the emperor’s other “superstitions.”[41] Frederick had a scribe’s hand cut off for spelling his name “Fredericus” instead of his preferred “Fridericus”; he had a man sealed and drowned in a winecask to demonstrate that the soul dies with the body (a point Salimbene counters with a flurry of scriptural citations); and he ordered one of his men go hunting, and the other to sleep through the day, and when the hunter returned, had them both cut open to see who had better digested his food. James IV was a famous polymath, well known for his mastery of many languages. Bada’uni in particular presented Akbar as such an irreligious tyrant that chunks of his history were repressed until after Akbar’s death. In part, these rulers are all said to carry out the deprivation experiment because cruel experimentation is what learned, excessively curious tyrants do. With all this in mind, we should not worry whether these stories could be true, straightforwardly, but neither should we simply dismiss them as untrue: rather we should assume that their “truth” is what the stories are interested in.

One key motive in these experiments is that of getting past culture and into a human behavior, trait, or characteristic that just is, automatically. That is, what the experiments seek is a cultural element—not only language, but a particular language, or a religion, or an ethnos—that comes into being without any need for cultural or even human support. Unlike the thought experiments of the Islamic theological novels by Ibn-Tufail (d. 1185) and Ibn al-Nafis (d. 1288)—which each have children spontaneously generated on remote islands, where each systematically and rationally, without cultural training, arrives at philosophical and religious truths[42]—the classical language deprivation experiment wants a truth that emerges from nowhere, freed from any train of causes, rational or otherwise. Unlike the isolation thought experiments that would proliferate in linguistic speculations in eighteenth-century Europe—in Bernard Mandeville’s 1729 Fable of the Bees,[43] the Abbé de Condillac’s 1749 Essai sur l’origine des connaissances humaines,[44] and Montesquieu’s Pensées,[45] among others—the classical thought experiment does not expect that the first language would be primitive or “savage,” but rather that it would be perfect, divine, or at the very least, identical with some culturally dominant language of the present. The eighteenth-century isolation experiment emerges from a European present increasingly certain of its own cultural supremacy and worldwide dominance; the earlier versions feature cultures that seek to ground themselves in something surer than their own momentary supremacy. The classical isolation experiment is thus driven less by a hunt for origins than by a hunt for foundations, a hunt that, moreover, wants to do without the ongoing, reciprocal, and uncertain work of cultural interchange, as if anything acquired by deliberation, desire, and compromise must be inherently suspect. In brief, the classical isolation experiment wants something impossible, a natural culture. It wants the benefits of language, ethnicity, and religion, all the supposedly “timeless” or “traditional” stuff of a “people,” without having to own up to the ongoing negotiations, historicity, and inadequacies of living through particular manifestations of these categories.

But what they tend to find instead, however, is the necessity of care, and the catastrophe of its absence, excepting one late version of the Akbar experiment, from François Catrou’s 1708 Histoire générale de l’empire du Mogol. Catrou bases his account on Niccolao Manucci’s 1698 History of Mughal India. Manucci has Akbar hunt not for religious but rather, simply, linguistic origins. Some thought it would be Hebrew, others “Chaldean,” likely meaning Aramaic, others Sanskrit, “which is their Latin.” Here Akbar provides no nurses, but rather commands only that no one, “under pain of death,” was to speak to the children or, notably, “to allow them to communicate with each other.” When the children turned twelve, they were questioned, but responded only by cringing, and remained “timid [and] fearful” for the rest of their lives.[46] Catrou reproduces all of this, with one enormous change. Being curious as to what language children would speak who had never learned any, and having heard that Hebrew was a “natural language” [“une langue naturelle”], Akbar shuts up twelve children with twelve mute nurses, and a male porter, also mute, who is never to open the doors of the “château” in which they have all been confined. The result:

When the children had reached the age of 12 years, Akbar had them brought into his presence. He then assembled in his Palace people skilled in all languages. A Jew who happened to be in Agra could judge if the children could speak Hebrew. It was not difficult to find in the capital Arabs and Aramaic speakers. On the other hand, the Indian scholars claimed that the children would speak the Sanskrit language, which they use as their Latin, and which is used only among the learned. They learn it to understand ancient books of Indian philosophy and theology. When the children appeared before the emperor, all were very astonished that they could not speak any language. They had learned from their nurse to get by without it. They expressed their thoughts only by gestures, which they used as words. In the end, they were so wild and so timid that it was a great deal of trouble to tame them, and to loosen their tongues, which they had made almost no use of in their childhood.

Quand les Enfans eurent attaint l’âge de douze ans, Akebar les fit venir en sa presence. Il rassembla alor dans son Palais des gens habiles en toutes les langues. Un Juif qui se trouvoit à Agra pouvoit juger si les Enfans parloient Hebreu. Il ne fut pas difficile de trouver dans la Capitale des Arabes & des Chaldéens. D’une autre part les Philosophes Indien prétendoient que les Enfans parleroient la langue Hanscrite qui leur tient lieu du Latin, & qui n’est en usage que parmi les Sçavans. On l’apprend pour entendre les anciens Livres de la Philosophie & de la Théologie Indienne. Lorsque ces Enfans parurent devant l’Empereur, on fut tout étonné qu’il ne parloient aucune langue. Ils avoient appris de leur Nourrice à s’en passer. Seulement ils exprimoient leurs pensées par des gestes qui leur tenoient lieu de paroles. Enfin ils étoient si sçauvages & si honteux, qu’on eut bien de la peine à les apprivoiser, & à délier leur langues, don’t ils n’avoient Presque point fait d’usage dans l’enfance.[47]

This is the very first time in the versions that cluster around Akbar that the children acquire language, and, barring the minimal account about James IV, the only time this happens in the whole tradition. Though pessimistic about the social training of the children, Catrou is surprisingly sympathetic to their language, using the same construction, tenir lieu, to act or substitute as, for both the relation of Sanskrit to Latin and sign to spoken language. The 1826 English translation notably misses this point. While it explains that Sanskrit “holds among them the same place, as does the Latin among the learned in Europe,” a correct translation, it then presents gestures as only “substitute signs for articulate sounds,” not quite incorrect, but incorrect in its erasure of Catrou’s own verbal echo; then it editorializes further with “they used only certain gestures to express their thoughts, and these were all the means which they possessed of conveying their ideas, or a sense of their wants.”[48] From Akbar’s perspective, this is a failure, as it is for Catrou’s first translator; for Catrou himself, perhaps not. From ours, one hopes, the story can be read as a kind of success, of the nurse and her charges circumventing the assumptions of the experiment to join together in a minority community, frustrating any expectations of foundation, origin, or the grandeur of a majority culture.

In all these experiments, we see that language, cultural specificity, religion, all these traits key to the “extra” or immaterial qualities that must accompany any animal that claims to be human, and any human recognized as belonging to the dominant human community, do not exist in some isolated, reasoning creature. Here there is no pure logos, no culture that just is. The human creature emerges in negotiated communion with others, in a shared time and space, or it doesn’t emerge at all. In Catrou’s version in particular, we have a language that cannot pretend to incorporeality, that, unlike spoken language and its written analog, cannot pretend so easily to be refined away from a particular body by impersonal abstraction. As the children have learned it from their nurse, neither does sign language function here as the first, primitive language—as in the “Linguistic Darwinism” hypothesized in the nineteenth century; rather it is a learned language, culturally developed and transmitted and worked out, collectively, sharing its present with Akbar, his court, and his experiment.[49] If the classical thought experiment wants to find the language that says “here language is,” or “here reason is,” or even “here is our culture, naturally,” if it wants to travel into the past to find the hidden truth that is still with us, what Catrou provides instead is a language that is an “here I am” enabled by a “here we are,” together, in the same time as any language, with as much truth, attesting to the need for care and recognition, in as impure and shifting a relationship as any community.

At least one question remains: apart from James IV, none of the rulers in the classical isolation experiment get what they want. Why should the story always be one of failure? The classical isolation experiment centers on tyrants; the story is about language, of course, but it is also, perhaps more so, sovereignty and its failed dreams. In wanting a culture or a language that just is, as a miracle, or pure decision, because it comes from nowhere and needs not justify itself to anything, the sovereigns are effectively seeking an analog to their own fantasies of sovereignty. But what the potentate witnesses, finally, is what he should have known all along: the impossibility of going it alone, and his own private helplessness, which can never be overcome, but which can only be shared.

[1] The Jewish writers Philo of Alexandria, Josephus, and pseudo-Philo (Liber antiquitatem biblicarum, whose Hebrew original dates to the first or second century, its Latin translation to the third or fourth) provide the earliest extant associations of Nimrod with Babel Tower. See Phillip Michael Sherman, Babel’s Tower Translated: Genesis 11 and Ancient Jewish Interpretation (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 170–71 and 178-81, and Karel van der Toorn and Pieter van der Horst, “Nimrod Before and After the Bible,” Harvard Theological Review 83, no. 1 (1990): 17–19. Augustine City of God XVI.4 and Bede, On Genesis, trans. Calvin B Kendall (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008), 230–31 are influential early Christian sites of transmission for this story.

[2] See also Genesis 3:22, the expulsion from Eden, and possibly 6:3, God’s response to the early longevity of humans and their admixture with the Nephilim, the “sons of God.”

[3] For an early parallel, dating to roughly 2000 BCE, Samuel Noah Kramer, “The ‘Babel of Tongues’: A Sumerian Version,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 88, no. 1 (1968): 108–11.

[4] Augustine of Hippo, On Genesis, ed. John E. Rotelle, trans. Edmund Hill (Hyde Park, New York: New City Press, 2002), for The Literal Meaning of Genesis, IX.9, page 387 (perhaps not worth finding it out, but perhaps survives to the present), and Two Books on Genesis against the Manichees, Book I, IX, 15; page 63 (“with God there is just sheer understanding, without any utterance and diversity of tongues”).

[5] For a set of citations, see Irven M. Resnick, “Lingua Dei, Lingua Hominis: Sacred Language and Medieval Texts,” Viator 21 (1990): 55–57.

[6] James C. VanderKam, trans., The Book of Jubilees (Louvain: Peeters, 1989), 3:28, 20-21; 12:25-26, 73. The text, originally written in Hebrew, survives largely in Ethiopic translations of the fourteenth through the twentieth centuries. For later, highly skeptical references to the language shared by humans and nonhumans, both written in Greek, see the first-century Confusion of Tongues by the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, On the Confusion of Tongues. On the Migration of Abraham. Who Is the Heir of Divine Things? On Mating with the Preliminary Studies, trans. F. H. Colson and George Whitaker, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932), 12–15, III; and also George Synkellos, The Chronology: A Byzantine Chronicle of Universal History from the Creation, trans. William Adler and Paul Tuffin (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 8, from the ninth century.

[7] Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge, trans., The Book of the Cave of Treasures (London: The Religious Tract Society, 1927), 132.

[8] Isidore of Seville, The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Stephen A. Barney et al. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007) XI.1, 191; Bede, On Genesis, 121.; AUGUSTINE CITY OF GOD XVI.11 – check

[9] Interrogationes et responsiones in Genesin, PL 100: 533D; for later repetitions, see the Genesis commentaries by Remigius of Auxerre, PL 131: 81B, and Angelomus of Luxeuil, PL 155: 167B.

[10] Letter 23, in Hildegard of Bingen, The Letters of HIldegard of Bingen, trans. Joseph L. Baird and Radd K. Ehrman, vol. 1 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 76–80. As tempting as it might be to identify the 1011 nouns and 23 letters Hildegard invented for her lingua ignota with this paradisiacal language, Sarah Higley, Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language: An Edition, Translation, and Discussion (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007), 29, observes that it “stretches credibility that names for… ‘excrement’ and ‘privy cleaner’ would be needed by the virgin throng in heaven.”

[11] Resnick, “Lingua Dei, Lingua Hominis,” 57, a foundational and thorough account of the development of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin as the three “holy languages” of Latin Christendom.

[12] John Carey, ed. and trans., Apocrypha Hiberniae II: Apocalyptica 1, In Tenga Bithnua, The Ever-New Tongue (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009), 113. For the date of the first recension, see 92.

[13] To be sure, Hebrew does not inevitably and always have this status for Christians: the Book of John Mandeville repeats the belief that Gog and Magog, the horrific Jewish tribe enclosed in Scythia by Alexander the Great, speak Hebrew, a language preserved by the remaining, unenclosed Jews, scattered homeless throughout the world, so they can lead these terrible people to ruin Christendom when they break out during the last days. John Mandeville, The Book of Marvels and Travels, trans. Anthony Bale (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 105.

[14] Herodotus, The Famous History of Herodotus, trans. B[arnabe] R[ich] (London: Thomas Marshe, 1584), folio 70, EEBO, STC / 216:06. The attribution to Rich is both traditional and also widely supposed to be incorrect.

[15] Margaret Thomas, “The Evergreen Story of Psammetichus’ Inquiry,” Historiographia Linguistica 34, no. 1 (2007): 37–62. For recent, reliable surveys of the primary texts, Deborah Levine Gera, Ancient Greek Ideas on Speech, Language, and Civilization (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 69–111, and Benjamin Eldon Stevens, “Not Beyond Herodotus: Psammetichus’ Experiment and Modern Thought about Language,” in Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond, ed. Jessica Priestley and Vasiliki Zali (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 278–97.

[16] I have been unable to consult its earliest editions (two in 1540, and another 10 years later); for the 1570 edition, easily available online, Pedro Mexía, Silua de varia lection (Seville: Hernando Diaz, 1570), Chapter XXV, folio 26r. For the French and English, Les diverses leçons de Pierre Messie, trans. Claude Gruget (Lyon: Gabriel Cotier, 1563), 139–40, and The Foreste or Collection of Histories, trans. Thomas Fortescue (London: William Jones, 1571), 22–23. The title page of the French 1576 edition likely omitted the Roman numeral L, resulting in an impossible claim for 1526 for its printing date, an error perpetuated by the metadata of the Gallica website of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

[17] Laurent Joubert, Erreurs populaires au fait de la médecine (Bourdeaux: Simon Millanges, 1578), 596; The Second Part of the Popular Errors, trans. Gregory David de Rocher (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007), 243. Joubert explains that he had written most of his discussion of this experiment—which begins with depositing two children with a mute nurse “en une forest, ou ils ne pouvoint ouïr aucune vois humaine” [575; in a forest, where they could not hear any human voice] –before having read Mexía.

[18] Félix Racine, “Herodotus’s Reputation in Latin Literature from Cicero to the 12th Century,” in Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond, ed. Jessica Priestley and Vasiliki Zali (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 195–96.

[19] Quintilian, The Orator’s Educaton, Volume IV: Books 9-10, ed. and trans. Donald A. Russell, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 257, X.1. For a hypothesis that Quintilian may be telling a version of the story independent of Herodotus, see Daniel J. Taylor, “Another Royal Investigation of the Origin of Language,” Historiographia Linguistica 11, no. 3 (1984): 500–502.

[20] “Bekeselêne,” Suda Online, accessed July 1, 2017, from a tenth-century Byzantine commentary. For further discussion, see Stevens, “Beyond Herodotus,” 287.

[21] He enjoyed a brief revival in the twelfth century; see James Jerome Murphy, Rhetoric in the Middle Ages: A History of Rhetorical Theory from Saint Augustine to the Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), 123–24.

[22] Carl P. Cosaert, The Text of the Gospels in Clement of Alexandria (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008), 13; Clement of Alexandria, Quis dives salvetur, ed. P. Mordaunt Barnard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1897), x.

[23] Chapter VIII, Tertullian, “Ad Nationes,” trans. Q. Howe, The Tertullian Project, 2007, http://www.tertullian.org/articles/howe_adnationes1.htm.

[24] BnF Latin 1622, the “Codex Agobardinus.” The Psamtik story is at 8v. He may have been drawing on Varro’s lost Antiquitates rerum humanarum et divinarum; see Racine, “Herodotus in Latin Literature,” 209.

[25] Roger Pearse, “Tertullian : Ad Nationes,” The Tertullian Project, December 11, 1999, http://www.tertullian.org/works/ad_nationes.htm.

[26] Salimbene de Adam, Chronica, ed. Oswald Holder-Egger, MGH, Scriptorum 22 (Hannover: Impensis bibliopolii Hahniani, 1905), 350. For a brief contextualization of this passage amid “signs, especially from the twelfth century onwards, of tenderness towards infants and small children,” Mary Martin McLaughlin, “Survivors and Surrogates: Children and Parents from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century,” in Medieval Families: Perspectives on Marriage, Household, and Children, ed. Carol Neel (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 39.

[27] Alas for my ignorance, all of this material currently exists only in Hebrew; for commentary, see especially Moshe Idel, Language, Torah, and Hermeneutics in Abraham Abulafia, trans. Menahem Kallus (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 15, 146–47, n73-75. A certain Obadiah the Prophet of Guratam tells a version in which a king performs the experiment twice, with a mixture of boys and girls, the first time with circumcised boys, the second, with uncircumcised: in both cases, the girls spontaneously produce Hebrew, but only in the first do the boys: see Gera, Greek Ideas on Speech, 94. Obadiah’s reference to a Jewish printing press elsewhere in his work indicates a post-medieval composition date; see Abraham Joshua Heschel, Prophetic Inspiration After the Prophets: Maimonides and Other Medieval Authorities, ed. Morris M. Faierstein (Hoboken: KTAV, 1996), 25. See also Umberto Eco, The Search for the Perfect Language, trans. James Fentress (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), 49–50.

[28] Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, The Historie and Cronicles of Scotland, ed. Aeneas James George Mackay, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1899), 237. The work first appears in print in 1728; for an early assessment of the story, Sir Walter Scott, Tales of a Grandfather: Being Stories Taken from Scottish History (Edinburgh: Cadell and Company, 1828), 219, “it is more likely they would scream like their dumb nurse, or bleat like the goats and sheep on the island.”

[29] Abul Fazl, Akbar’s own court historian, began the work, but was murdered (in 1602) before he could complete it. Vol III? Chapter 68? Next volume coming out Jan 2018. Stuck with old translation.

[30] Mobad Shah [Muhsin Fani, attributed], The Dabistán, or School of Manners, trans. David Shea and Anthony Troyer, vol. 3 (Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, 1843), 90–91. No more recent English translation yet exists; according to the assessment of Carl W. Ernst, “Situating Sufism and Yoga,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 15, no. 1 (2005): 41 n111, the Shea and Troyer is at times “hopelessly incorrect.”

[31] For the two slightly divergent English translations, Abd-Ul-Qadir bin Maluk Shah [Al-Badaoni], Muntaḵẖabu-T-Tawārīḵẖ, trans. W. H. Lowe, vol. 2 (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1884), 296; H. M. Elliot, The History of India as Told by Its Own Historians, ed. John Dowson, vol. 5 (London: Trübner and Co., 1873), 533.

[32] Giovanni Battista Peruschi, Informatione del Regno, et Stato del Gran Re di Mogor (Rome: Luigi Zannetti, 1597); Historica relatio, de potentissimi regis Mogor (Mainz: Heinrich Breem, 1598).

[33] Anon., A True Relation without All Exception, of Strange and Admirable Accidents, Which Lately Happened in the Kingdome of the Great Magor (London: Thomas Archer, 1622), 5–7. The earliest version of the ape story might be that of Thomas Roe, The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mogul, 1615-1619, ed. William Foster, vol. 2 (London: Hakluyt society, 1899), 318. See also Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes, vol. 1 (London: William Stansby, 1625), 587.

[34] E. D. Maclagau, “Jesuit Missions to the Emperor Akbar,” Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 65 (1896): 77. No single-volume translation, or even edition, of Xavier’s correspondence seems to exist. This religious version of the story also appears in Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes, 5:516, which concludes “For as they spake no certaine Languge, so is not hee setled in any certaine Religion.”

[35] For examples of mixing this story with Herodotus, Christoph Besold, De Natura populorum (Tübingen: Philibert Brunni, 1632), 57, which, like Xavier, has Akbar conduct a religious experiment; August Pfeiffer, Introductio In orientem (Wittenberg: Daniel Schmatz, 1671), 8, citing Besold, but adds that the Hebrew masters at Akbar’s court insisted that Hebrew was “implanted naturally” (“naturaliter impantatam”) in the first human. In neither of these, Xavier included, are the nurses and guards deaf; they are only commanded not to speak.

[36] For example, a 1632 entry in the journal of the English traveler Peter Mundy, excerpted in Michael H. Fisher, ed., Visions of Mughal India: An Anthology of European Travel Writing (London: I.B.Tauris, 2007), 78, where the nurses are mute. Ole Borch, cited below, and Christian A. Ludwig, Brevis commentatio de proprietate nominum (Geneva: M. Christiano – Augusto Ludwig, 1730), 13, which quotes the Borch exactly, are effectively secular, both because of their context of linguistic speculations and because their brevity trims away Akbar’s motivations.

[37] Daniel Sennert, Paralipomena (Lyon: Jean Antoine Huguetan, 1643), 76. For a similar point, see Isaac Cardoso, Philosophia Libera (Venice: Bertano, 1673), 648, which cites Jesuit letters as its source, and adds that not even birds can sing without being taught.

[38] Ole Borch, De causis diversitatis linguarum (Copenhagen: Daniel Paul, 1675), 1, whose first page mixes this story with Herodotus and Akbar.

[39] Most frustrating of these may be Gera, Greek Ideas on Speech, because it is by far the most learned study of the Herodotus tale; but she talks about it as if it were historically true, for example, at 78, “Perhaps only ordinary people could be compelled by the king to hand over their children for experimental purposes.” At 71, she argues that bekos sounds Egyptian, and the experiment seems more Greek, “more specifically, Ionian,” than Egyptian; by contrast, Arno Borst, Der Turmbau von Babel: Geschichte der Meinungen über Ursprung und Vielfalt der Sprachen und Völker, 4 vols. (Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann, 1959), 1:40, determines that “the formulation of the question is Egyptian and not Greek” [“die Fragestellung ist ägyptisch und nicht griechisch”]. Other dismaying responses include Michael Davis, The Soul of the Greeks: An Inquiry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 80, which scoffs at the Herodotus story as “utterly preposterous” and faults Psamtik’s reasoning; Marcel Danesi, Vico, Metaphor, and the Origin of Language (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 6, judges the experiment “clearly preposterous and bizarre”; Debra Hamel, Reading Herodotus: A Guided Tour through the Wild Boars, Dancing Suitors, and Crazy Tyrants of the History (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2012) disapproves of “Psammetichus’ peculiar brand of child abuse”; Seth Benardete, Herodotean Inquiries (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 2012), 33, faults the experiment for its design, including its failure to distinguish between logos and glossa. Less distressing, because it originates outside cultural history, is John D. Bonvillian, Amanda Miller Garber, and Susan B. Dell, “Language Origin Accounts: Was the Gesture in the Beginning?,” First Language 17 (1997): 219–39, which pairs its doubt of the Psamtik story with certainty about Akbar’s. Stevens, “Psammetichus” deserves praise, however, both for correctly understanding the Herodotus account as mythic, and also for detecting a sublimated desire in some linguistics scholarship to be able to perform the experiment.

[40] For example, Pliny, Natural History, trans. D. E. Eichholz, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 67, XXXVI.19.

[41] Salimbene de Adam, Chronica, 350–53.

[42] Ibn Tufail, Hayy Ibn Yaqzan, trans. Lenn Evan Goodman (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Ibn al-Nafīs, The Theologus Autodidactus, ed. and trans. Max Meyerhof and Joseph Schacht (Oxford: Clarendon, 1968). The former, translated into Latin at Oxford in 1671 as Philosophus Autodidactus, exerted no small influence on European Enlightenment speculations about the origins of language, although neither Ibn Tufail nor Ibn al-Nafis are themselves much interested in the topic. Their autodidacts each acquire language through teachers, and that only long after they have reasoned their way on their own far into major philosophical truths.

[43] Bernard Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees, ed. Irwin Primer (New York: Capricorn Books, 1962), 261–62.

[44] Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, An Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge, trans. Thomas Nugent (London: J. Nourse, 1756), Part II, Chapter 1, 171–79.

[45] Charles-Louis Montesquieu, My Thoughts, trans. Henry C. Clark (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012), 51, #158. Clark bases his translation on Louis Desgrave’s definitive French edition of Montesquieu’s complicated notebooks, which date from 1720 until his death.

[46] Niccolo Manucci, Storia do Mogor; Or, Mogul India 1653-1708, trans. William Irvine, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1907), 142.

[47] François Catrou, Histoire generale de l’empire du Mogol depuis sa fondation (The Hague: Guillaume de Voys, 1708), 137.

[48] The anonymous translation compiled as Niccolao Manucci and François Catrou, History of the Mogul Dynasty in India (London: J.M. Richardson, 1826), 117.

[49] For discussions of Romantic, then Darwinist treatments of signing as the original, primitive, natural, or animal language, concentrating largely on the nineteenth century, Douglas C. Baynton, Forbidden Signs: American Culture and the Campaign Against Sign Language (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 36–55; and Jennifer Esmail, Reading Victorian Deafness: Signs and Sounds in Victorian Literature and Culture (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2013), 102–32, who offers several such observations from mid-nineteenth-century language theorists: “Language…becomes grander, more dignified and more complex as it becomes less dependent on the body” (125).

Johann Conrad Amman, Surdus loquens (Leiden: Johannes Arnoldus Langerak, 1727), 2, a handbook for teaching the deaf to speak, originally published in 1692, and translated incompletely into English a year later, provides an anticipation of such sentiments in Catrou’s era, with its paean to the voice as the very breath of God: “and how little the deaf differ from beasts” [“quamque parum a brutis animantibus different”]. For further discussion, H-Dirksen Bauman, “Listening to Phonocentrism with Deaf Eyes: Derrida’s Mute Philosophy of (Sign) Language,” Essays in Philosophy 9, no. 1 (2008): n.p; Harlan Lane, When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf (New York: Random House, 1984), 100–101, which led me to the Amman; and especially Rebecca Sanchez, Deafening Modernism: Embodied Language and Visual Poetics in American Literature (New York: New York University Press, 2015), whose interest in “nonverbal communication” as resisting the “particular distaste for bodies in some branches of modernist writing” (68), as well as her engagement with queer theory and care ethics (eg, 48-61), is allied to my project here.